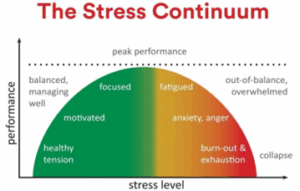

Stress is a universal experience—something we all encounter throughout our lives. Yet not all stress is harmful. In fact, some stress can be incredibly beneficial. The key lies in understanding the difference between eustress and distress. While both are responses to a perceived challenge or demand, and result in the burning of energy to return to homeostasis, their effects on our well-being and performance differ dramatically.

Stress is a universal experience—something we all encounter throughout our lives. Yet not all stress is harmful. In fact, some stress can be incredibly beneficial. The key lies in understanding the difference between eustress and distress. While both are responses to a perceived challenge or demand, and result in the burning of energy to return to homeostasis, their effects on our well-being and performance differ dramatically.

Eustress is the term used for “positive stress.” It is the kind of stress that motivates, sharpens focus, and enhances performance. This response often arises in situations where the challenge is within our perceived coping abilities—such as preparing for a presentation, starting a new job, or training for a race. Eustress engages the sympathetic nervous system just enough to heighten awareness and energize the body without overwhelming it. Neurochemically, it moderates levels of adrenaline and dopamine, possibly increasing attention, memory, and goal-directed behavior. Emotionally, eustress is often accompanied by feelings of excitement, anticipation, and confidence. In educational, professional, or athletic settings, eustress can promote resilience, growth, and peak performance.

In contrast, distress is the harmful form of stress that occurs when demands exceed our perceived ability to cope. Whether triggered by chronic workload, interpersonal conflict, or sudden traumatic events, distress activates the same biological systems—but often too intensely or for too long. Prolonged exposure to cortisol, a hormone released during stress, can lead to fatigue, memory problems, sleep disruption, and weakened immunity. Psychologically, distress is linked to anxiety, irritability, and a sense of helplessness. Instead of motivating action, it can paralyze decision-making and diminish performance. Left unmanaged, chronic distress is a risk factor for serious physical and mental health conditions, including heart disease, depression, and burnout.

The distinction between eustress and distress is not just academic—it has practical implications for how we design our environments, set expectations, and support ourselves and others. For example, students or employees thrive when challenges are meaningful, achievable, and accompanied by encouragement and support. The right amount of stress, at the right time, can stretch our limits and spark personal growth.

The distinction between eustress and distress is not just academic—it has practical implications for how we design our environments, set expectations, and support ourselves and others. For example, students or employees thrive when challenges are meaningful, achievable, and accompanied by encouragement and support. The right amount of stress, at the right time, can stretch our limits and spark personal growth.

In summary, stress is not inherently good or bad. It is our energy level and our response to stressors that determine the outcome. By fostering eustress and minimizing distress, we can harness the energy we need to capitalize on stressors as a catalyst for learning, resilience, and well-being.

Cognitive Dynamics can help with productively potentiating stress.

Leave A Comment